(The following review is written and edited by Zenovia Toloudi)

Can form be the result of natural forces? According to Christopher Alexander probably. In Hans Haacke 1967 exhibition, the artifacts definitely flirt with these forces: They capture and map the immaterial elements of the environment: wind, light, motion, and gravity, through the manipulation of elements like nature/ soil, textile, and liquids.

“Hans Haacke 1967″ exhibition currently at MIT List Visual Arts Center.Image found: NYARTS magazine

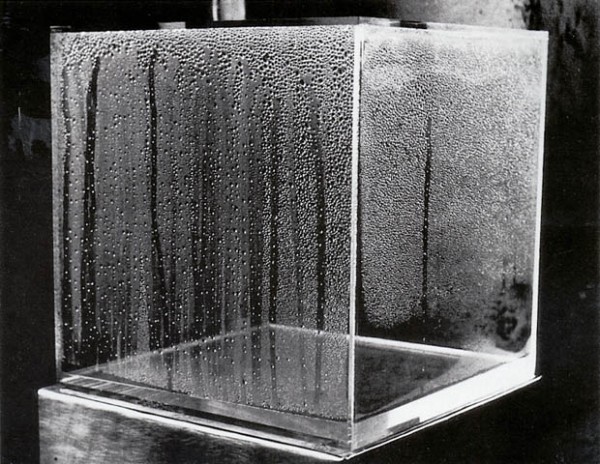

According to MIT List Visual Arts Center: “Haacke initially was involved with physical and biological systems: living animals, plants, and physical states of water and wind.” Many interested in art may know the famous Condensation Cube. Art Historian Caroline Jones, organizer of the exhibition, says at NYARTS Magazine : “In his early work, Haacke’s use of water and air was influenced by his involvement with Group Zero , an international group of artists interested in finding new and often kinetic materials with which to make art.”

Condensation Cube 1963 by Hans Haacke. Image found: Artnet

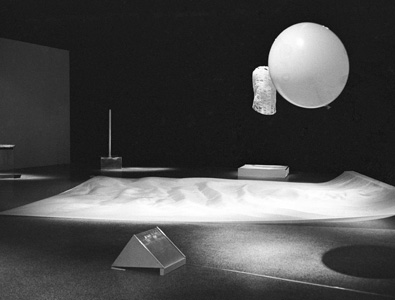

The exhibition space resembles in a way the ideal dreamy setting usually found in a child’s drawing: it is a symbolic, abstract representation of the environment: there is sun, sea, hill and some man-made objects around. In this stage, one can observe patterns of change, rhythms of aliveness. Things are simple but interesting, scientific but humorous, rich in form but never stable.

The exhibition at 1967. Image found: MIT List Visual Arts Center

In this either poetic or pragmatic, but definitely energetic, field, it is hard to create barriers between the natural and artificial states of things and forces. What is the role of technology in this human-made landscape? From one hand the natural wind comes out of a machine, the fan, and the natural green is geometrized in a conic configuration. This machinic nature (of the fan, the motor, the pre-cut or industrial volume to host the liquid, the growing grass, the seeds to be grown) constantly shapes the intangible, the forgotten (in the industrial time of the 60s), immaterial elements of space. From the other hand the man-made fabric fluctuates in space like waves, and the hellion balloon fights with gravity, both shouting towards the creation of well crafted objects allowing the existence of blowing masses, Zephyrean fields, airy movements, soft sounds, repetitive rhythms, and other phenomena that are usually unobservable. So, is it all about the making of an anti-technological form, a back to the nature call?

How much artificial reaches the real? At the end it does not matter. Both natural and artificial states participate in the construction of a constantly evolving landscape. Similar play among the two can be found in Olafur Eliasson’s recent work where natural phenomena are constructed through artificial means. Nature grows in artificial forms. Although it is been said there is no such thing as artificial nature, it is just nature.

Hans Haacke 1967. Image found: Daily serving

The design of the exhibition itself plays with this idea of nature: The differentiated ambience to that of the dark Lightballett (in next room) where life, as light, is born in darkness, it evolves in this room. Also, the reveal of the -usually covered- window in the gallery participates in this natural-artificial dialogue by reminding the presence of the real nature, one of the MIT outdoor yards.

One’s isolation in the environment of the desktop, and work-life detachment from the fields of nature, request the need for space to be the apparatus that will map the ever-changing conditions of the world. How can one slow down to observe that the ice is melting, or that the heat is way too strong or that I am in a recreated refrigerating condition somewhere in the desert? How can one rethink the space deriving out of these intangible elements, how can one design the soft envelope, sensitive enough to capture and expose all those temporal changes? Where energy is being hold and released in space? How can one feel this when passing through the space, and therefore how can one expand her personal bubble? As Jonathan Hill says in the Immaterial Architecture: “My concern is not the immaterial alone or the immaterial in opposition to the material. Instead, I advocate an architecture that embraces the immaterial and material”.

About Hans Haacke:

Hans Haacke was born in Cologne, Germany in 1936 and has been based in New York since 1965. He studied at the “Staatliche Werkakademie” in Kassel, Germany, from 1956 to 1960, and then from 1961 to 1962 at the Tyler School of Fine Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. From 1967 to 2002, he was Professor at the Cooper Union in New York, USA. He has received numerous prizes, including the Golden Lion of the Biennale di Venezia in 1993 (with Nam June Paik).

Resources:

MIT List Visual Arts Center

Artist talk

Immaterial Architecture by Jonathan Hill